|

(« back to home

page)

English Church Architecture.

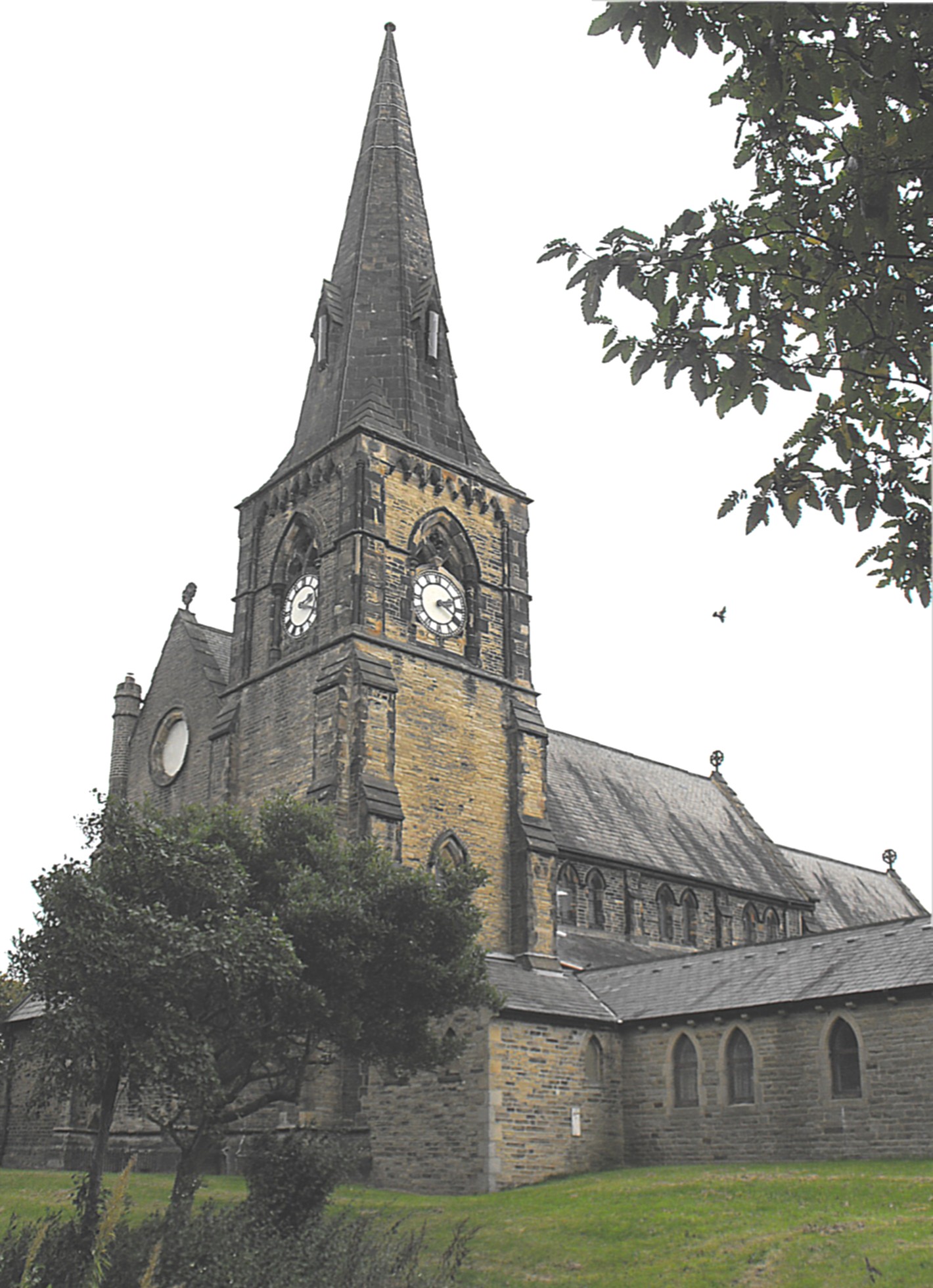

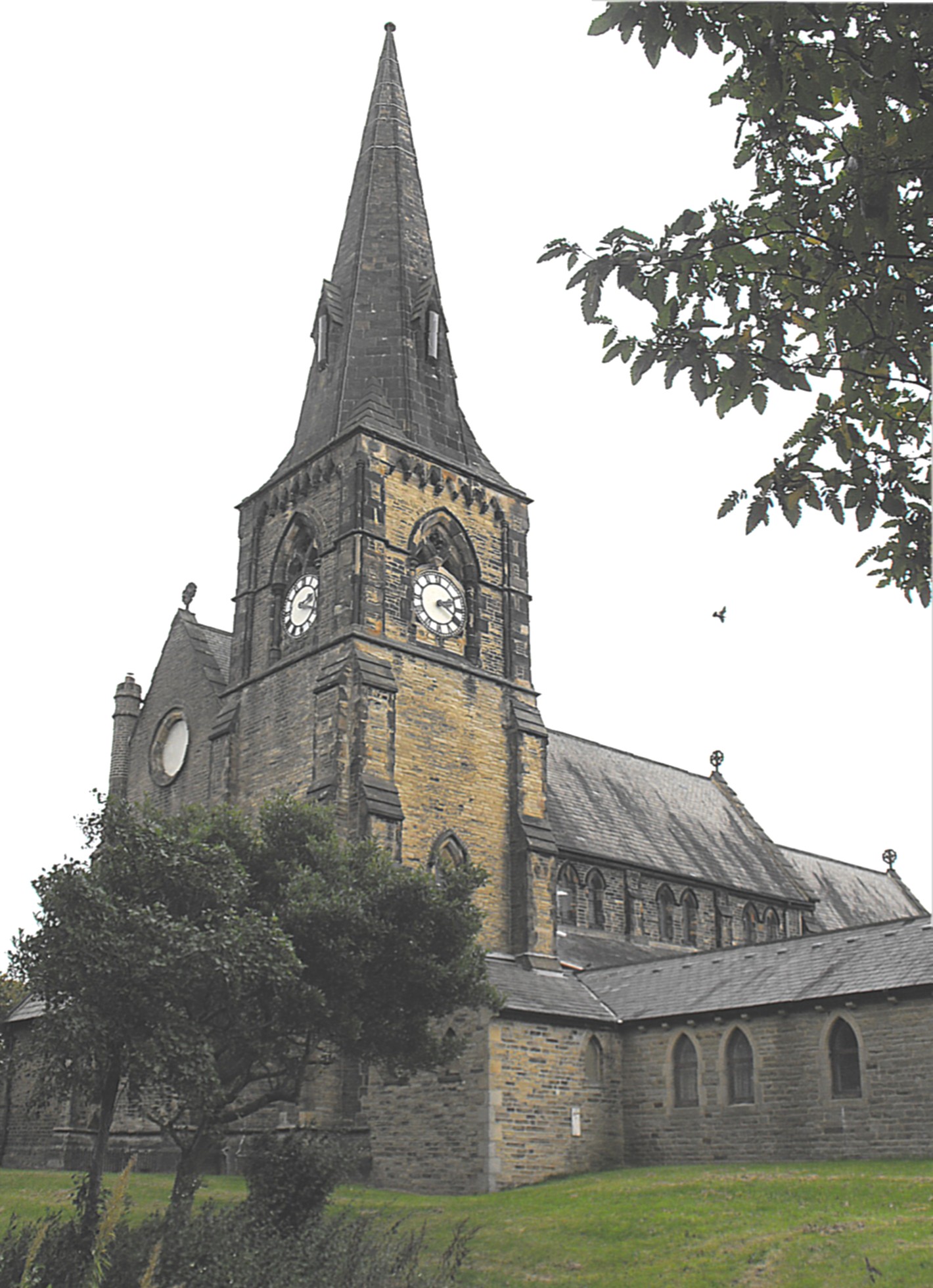

WYKE,

St. Mary

(SE 151 267),

CITY OF BRADFORD.

(Bedrock:

Carboniferous Westphalian Series, Clifton Rock from the Lower Coal

Measures.)

The second

church designed by the West Yorkshire architect,

James Mallinson

(1818-84).

|

One of the subjects examined by this

web-site is the near-complete oeuvre of a little-known but regionally

dominant, mid-nineteenth century architectural firm specialising in

ecclesiastical work, in order to discover how they built their local reputation,

how they maintained a financially competitive edge and sustained a very busy

practice with few or no staff, and what 'success' looked like in terms of

monetary reward and the provincial architect's acquired position in

Victorian society. The firm chosen is the partnership between James

Mallinson and Thomas Healey (fl. 1845-62/3), who worked out of offices in

Halifax and Bradford. The majority of the extant church buildings for which the

partners were responsible are listed below and should ideally be examined in

chronological order. They are:

|

1. Queensbury, Holy Trinity

(Bradford) (1843) (Mallinson

alone) |

19. East Keswick, St. Mary Magdalene

(Leeds) (1856) |

|

2. Wyke, St. Mary (Bradford)

(1844) (Mallinson alone) |

20. Claremount, St. Thomas (Calderdale)

(1857) |

|

3. Clayton, St. John the Baptist

(Bradford) (1846) |

21. Clifton, St. John (Calderdale)

(1857) |

|

4. Baildon, St. John the Baptist

(Bradford) (1846) |

22. Salterhebble, All Saints

(Calderdale) (1857) |

|

5. Manningham, St. Paul (Bradford)

(1846) |

23. Thornaby-on-Tees, St. Paul

(Stockton-on-Tees) (1857) |

|

6. Mytholmroyd, St. Michael

(Calderdale) (1847) |

24. Thornhill Lees, Holy Innocents

(Wakefield) (1858) |

|

7. Bankfoot, St. Matthew (Bradford)

(1848) |

25. Bugthorpe, St. Andrew (East Riding)

(1858) (nave only) |

|

8. Shelf, St. Michael & All Angels

(Bradford) (1848) |

26. Bowling, St. Stephen (Bradford)

(1859) |

|

9. South Ossett, Christ Church

(Wakefield) (1850) |

27. Girlington, St. Phillip (Bradford)

(1859) |

|

10. Barkisland, Christ Church

(Calderdale) (1851) |

28. Lower Dunsforth, St. Mary (North

Yorkshire) (1859) |

|

11. Boroughbridge, St. James (North

Yorkshire) (1851) |

29. Welburn, St. John (North Yorkshire)

(1859) |

|

12. Langcliffe, St. John the Evangelist

(North Yorkshire) (1851) |

30. Ilkley, All Saints (Bradford) (1860)

(chancel only) |

|

13. Cundall, St. Mary & All Saints

(North Yorkshire) (1852) |

31. Horton, All Saints (Bradford)

(1862) |

|

14. Heptonstall, St. Thomas the Apostle

(Calderdale) (1853) |

32. Hepworth, Holy Trinity (Kirklees)

(1862) |

|

15. Mount Pellon, Christ Church

(Calderdale) (1854) |

33. Dewsbury, St. Mark (Wakefield)

(1862) |

|

16. Thorner, St. Peter (Leeds) (1854)

(partial reconstruction) |

34.

Heaton, St. Barnabas (Bradford) (1863)

(Mallinson with T.H. Healey)

|

|

17. Withernwick, St. Alban (East Riding)

(1854) (reconstruction) |

35. Tockwith, Church of the

Epiphany (North Yorkshire) (1863) (as

above) |

|

18. Mappleton, All Saints (East Riding)

(1855) (not the tower) |

|

|

Fortunately,

following Mallinson's limited success with his work at Queensbury, he

received another three commissions before any shortcomings at Holy

Trinity had had time to show up, namely for a new church at Wyke and for

National Schools at Manningham and Elland. Mallinson was working

on the designs for St. Mary’s, Wyke, in 1844 but progress appears to

have been slow. The site was a long time in preparation for, as

the Rev. William Houlbrook explained in a letter to the Incorporated

Church Building Society on the 30th November 1844 (Lambeth Palace

Archives, ICBS 3529) 'its stability [was] endangered by the mines which

have already been opened or may be opened near it'. However Mallinson

himself seems to have been partly responsible for the

delay himself for in his next letter on the 8th January 1845 (Lambeth

Palace Archives, ICBS 3539), Houlbrook complained of Mallinson’s failure to

complete the work promptly and apologised for his own miscalculation of

the church’s expected accommodation. J.H. Good, the Incorporated

Church Building Society's architect, did not

respond to either of these points directly in his reply but stated that before any

grant could be awarded: (i) the plans would have to be amended to

increase the thickness of the clerestory walls; and (ii) an additional

drawing would have to be submitted to his office showing the proposed

construction of the aisle roofs on a scale of half an inch to the foot.

This was possibly no more than Good's customary display of awkwardness

but Mallinson may also have been struggling a little. He was

simultaneously drawing up plans and elevations for Elland National

School, the original set of which in neat Tudor style, are signed and

dated March 1845 (as may be seen in the Victoria & Albert Museum RIBA

collection, cat. PB432/18), yet neither this nor St. Mary's church appear

to have been completed until after Mallinson formed his partnership with

Thomas Healey in June or July since a second set of drawings of the

school exists also, dated August 1845 and signed this time by Mallinson and

Healey. Additions and revisions include a bell-côte over

the cross-gabled central bay, a decorative chimney stack at the

southwest angle, a fan-light above the door, and a dripstone over the

three-light transomed upper window, to say nothing of a datum line.

It is, of course, impossible to tell whether these alterations were due

to Healey or represented second thoughts by Mallinson but the second set

certainly shows greater refinement. Fortunately,

following Mallinson's limited success with his work at Queensbury, he

received another three commissions before any shortcomings at Holy

Trinity had had time to show up, namely for a new church at Wyke and for

National Schools at Manningham and Elland. Mallinson was working

on the designs for St. Mary’s, Wyke, in 1844 but progress appears to

have been slow. The site was a long time in preparation for, as

the Rev. William Houlbrook explained in a letter to the Incorporated

Church Building Society on the 30th November 1844 (Lambeth Palace

Archives, ICBS 3529) 'its stability [was] endangered by the mines which

have already been opened or may be opened near it'. However Mallinson

himself seems to have been partly responsible for the

delay himself for in his next letter on the 8th January 1845 (Lambeth

Palace Archives, ICBS 3539), Houlbrook complained of Mallinson’s failure to

complete the work promptly and apologised for his own miscalculation of

the church’s expected accommodation. J.H. Good, the Incorporated

Church Building Society's architect, did not

respond to either of these points directly in his reply but stated that before any

grant could be awarded: (i) the plans would have to be amended to

increase the thickness of the clerestory walls; and (ii) an additional

drawing would have to be submitted to his office showing the proposed

construction of the aisle roofs on a scale of half an inch to the foot.

This was possibly no more than Good's customary display of awkwardness

but Mallinson may also have been struggling a little. He was

simultaneously drawing up plans and elevations for Elland National

School, the original set of which in neat Tudor style, are signed and

dated March 1845 (as may be seen in the Victoria & Albert Museum RIBA

collection, cat. PB432/18), yet neither this nor St. Mary's church appear

to have been completed until after Mallinson formed his partnership with

Thomas Healey in June or July since a second set of drawings of the

school exists also, dated August 1845 and signed this time by Mallinson and

Healey. Additions and revisions include a bell-côte over

the cross-gabled central bay, a decorative chimney stack at the

southwest angle, a fan-light above the door, and a dripstone over the

three-light transomed upper window, to say nothing of a datum line.

It is, of course, impossible to tell whether these alterations were due

to Healey or represented second thoughts by Mallinson but the second set

certainly shows greater refinement.

St. Mary’s, Wyke, was not finally complete until 1847. Again, it is

difficult to rule out a possible contribution from Healey later in its

development but what is certainly clear is that the building represents is a definite advance on Holy Trinity,

Queensbury. The proportions are better: the nave is not as

tall and the width of the arcade piers is in better proportion to their

height. As for the nave roof, although there is an affinity with Holy

Trinity, it betokens greater stability due to the inclusion of two

pairs of purlins, ⅓ and ⅔ of the way up the pitch, and

of collar beams

connecting the lower purlins instead of tie beams crossing between the

wall plates, lifting the support higher towards the ridge. Moreover,

also at St. Mary's, the structural challenge has now been met of

surmounting the tower with a spire and an aesthetically successful one

at that. Discounting modern additions, the church comprises a

three-bay chancel with a N. organ chamber and a small S. chapel, and a

five-bay nave with lean-to aisles, a southwest tower occupying the

westernmost bay of the S. aisle, and a cross-gabled in the equivalent

position to the north.

Stylistically, as at

Queensbury, Mallinson adopted

a severe First Pointed (Early English) mode for his new building, which

is lit entirely by lancets

(albeit sometimes grouped or paired, as in the clerestory, or enriched with an order of shafts in shaft-rings at

the sides), notwithstanding that the preferred style of the

influential and censorious Ecclesiological Society was currently the flowing Second Pointed

(Decorated). Perhaps this was due to the fact that he

considered First Pointed provided more scope for economy, though he may also have

been glad to eschew complicated window traceries.

Inside the church, the four-bay nave arcades are composed of

double-flat-chamfered arches supported on alternately circular and

octagonal piers and join to the west the southwest tower

(there is no tower arch) and the cross-gabled vestry. (See

the photograph of the church interior, looking west, above.) The

chancel arch carries a roll on the outer order and two minor rolls

on each side of the inner order, above two orders of side shafts

with deeply carved stiff leaf capitals. The arch from the N.

aisle to the organ chamber and from the S. aisle to the chapel each

carry two flat chamfers

that die into the jambs. The nave roof

(shown below, looking west)

has purlins at the ⅓ and ⅔

stages,

collars joining the lower purlins supported by arched braces below,

and struts rising from the collars to the second purlins above.

Unusually, the aisle roofs also have two tiers of purlins, and are

braced against the arcades. The chancel roof is similar.

Decorative work in the building includes the simple

but attractive marble tiling patterns on the floors and on the steps leading up to the

sanctuary (as illustrated below

left). The font (below right) is probably original

and has trefoil-cusped arches around the circular bowl, separated by

diminutive shafts, while the bowl itself is supported on the usual five

shafts, comprising one large one in the centre surrounded by four with

moulded capitals and bases.

On 10th May, 1845, James Mallinson married Mary Waddington, the youngest

of three daughters of Samuel Waddington, landlord of the Black Swan, at

St. Martin's, Brighouse. Probably he expected shortly to have a family,

and he would doubtless have reflected on the pressures he was

experiencing, his income, and his prospects for the future.

This may have appeared the time to expand his business. By

some means or other, he knew or knew of another Yorkshireman who needed to advance himself

and who for the past sixteen years had been helping to design churches

in Worcester...

|