|

CIRENCESTER, St. John the Baptist (SP 023 021), GLOUCESTERSHIRE. (Bedrock: Middle Jurassic, Cornbrash Formation.)

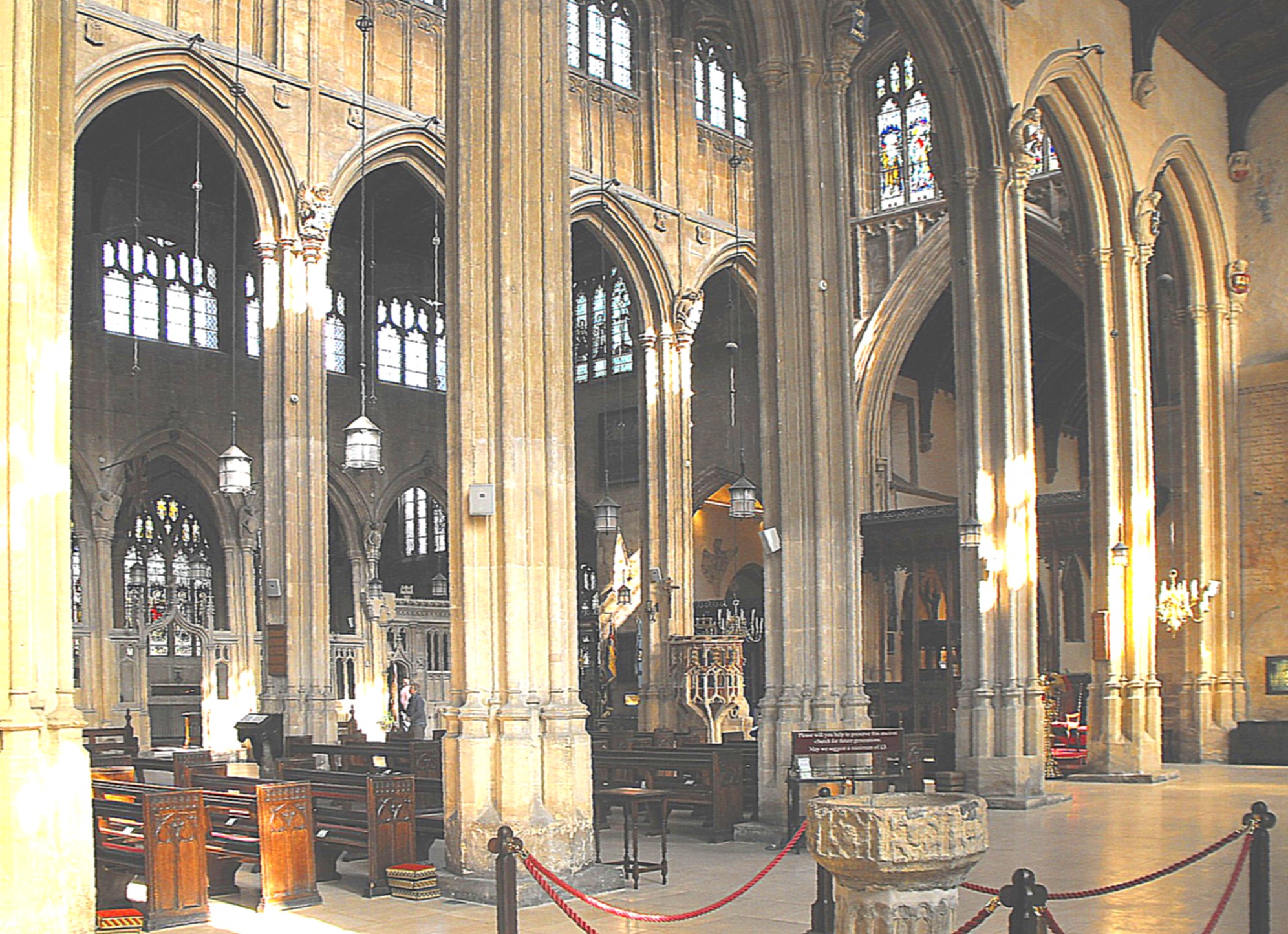

One of the largest and most important Perpendicular churches in England.

This is a huge and magnificent building and it is surprising to discover that the nave appears to have been almost as long when the church was first built in the middle of the twelfth century. It was then probably cruciform in plan (or, more precisely, pseudo-cruciform, which is to say it had transepts but no true crossing), with transepts that would later determine the width of the nave aisles. Remnants of twelfth, thirteenth and early fourteenth century work are still to be found at the east end if the church, where they include the two-bay Norman-Transitional arcade between the chancel and S. chapel, formed of semicircular responds and a round central pier with a primitive stiff leaf capital supporting triple-flat-chamfered arches that may or may not be precisely contemporary. The untraceried east windows to the chancel and S. chapel (seen above in the view of the church from the east) are composed of stepped trefoiled lights in the style of c.1300, but the dogtooth moulding around the dripstone of the former suggests this window at least may be an earlier one remodelled. The arcade between the chancel and St. Catherine's Chapel to the north comprises two double-flat-chamfered arches rising from a central octagonal pier and semi-octagonal responds, which would fit any date from the thirteenth century to the fifteenth.

Be that as it may, however,

what is clear is that St. John the Baptist's church today appears almost totally

mid-to-late Perpendicular, with a visual emphasis laid firmly on its width

rather than its length (as illustrated by the interior photograph above,

looking northeast from the southwest corner of the S. aisle) and its extraordinary S.

porch. The building plan needs to be carefully set out, especially

to the east, where three chapels run parallel with the chancel:

the wide but short S. chapel opening from the chancel's two western

bays; St. Catherine's Chapel, running the full length of the chancel to

the north;

The W. tower was erected about a hundred

years before the porch, around 1400. It rises in three stages to

traceried battlements and crocketed pinnacles,

supported by angle buttresses to the southwest and northwest, and flying

buttresses to the southeast and northeast, which leap down and out to

cross the west walls of the aisles. The tower W. window is five-light,

with supermullioned tracery, subarcuation of the outer lights in pairs,

and strong mullions

The nave, aisles, Trinity Chapel and Lady Chapel are embattled, with blank tracery decorating the battlements everywhere except over the nave, which has openwork battlements, and pinnacles between the bays, which create a veritable forest when the building is viewed from the north or northeast. The clerestory windows, and the north and south aisle windows (albeit there is only room for one such window in the N. aisle, to the west of the porch), are wide and four-light, with supermullioned tracery and transoms at two levels beneath exceptionally depressed four-centred arches. The more conventional Trinity Chapel windows are two-centred. The Lady Chapel has two-centred, three-light windows to the north, and a less satisfying five-light, four-centred window to the east, with supermullioned tracery and supertransoms St. Catharine's Chapel has a four-light E. window with exceptionally deep, dropped supermullioned tracery, which extends halfway down the height of the window.

Inside the church again, the nave arcades

are composed of very tall piers formed of eight shafts separated by deep

notches with very narrow bowtells in the re-entrants (see the photograph below

left), supporting arches of complex profile arranged in two orders.

Narrow shafts emerging from behind large carved angels at the base of

the arcade spandrels, rise to separate the three-light clerestory

windows, each formed of a glazed upper section and a lower stone section

decorated with blank arcading, while more blank arcading decorates the spandrels of

the very tall chancel arch, upon

St. Catherine's Chapel and the Lady Chapel

are each entered through arches set in the E. wall of the N.

aisle. The former (seen on the right in the photograph below right),

as previously mentioned, largely comprises an infilling of the earlier

gap between the chancel and Lady Chapel, with all the concomitant

problems in illumination that brought with it, and is covered by

another attractive fan vault which David Verey nevertheless described as

'an uncomfortable fit for, in truth, it does appear somewhat

squashed in this decidedly narrow space (David Verey & Alan Brooks,

The Buildings of England: Gloucestershire Cotswolds, New Haven &

London, Yale University Press, 2002, p. 249). The Lady Chapel has an

exceptionally low-pitched roof and a large monument against the N. wall

of its sanctuary, commemorating a certain Humfry Bridges (d. 1598), and

Elizabeth, his wife (d. 1620), featuring two reclining figures

beneath a round coffered arch, supported beneath by what appear to be

their six daughters (three facing east and three west), while on either

side, a son kneels at a prayer desk beneath a flat-roofed 'extension'

surmounted by an obelisk. Equally striking, however, is the large

monument at the west end of the S. aisle, showing two figures holding

hands over another prayer desk, this time set between two Corinthian

columns and supported below by two only slightly smaller figures,

presumably the couple's daughters,

|

and the Lady Chapel, aligned further to the north alongside St.

Catherine's Chapel, with which it now communicates through an arcade

formed of three narrow bays but which once stood largely apart from the

chancel during an earlier period when St. Catherine's chapel was only a single

bay in length. The aisled nave is six bays long and flanked

alongside the four eastern bays of the N. aisle, by a fourth chapel,

known as the Trinity Chapel, which is divided from the aisle internally

by an elaborate stone screen (illustrated right).

Immediately west of the Trinity Chapel, a porch leads into the

penultimate aisle bay to the west, while the

tower adjoins the west end of the nave in the usual manner and soars up

to a height of 162' (49 m.) (Simon Smith & Derek Barnard, The Parish

Church of St. John the Baptist, Cirencester, Much Wenlock, R.J.L.

Smith & Associates, undated, inside cover), making it visible above the

roof-tops from all the surrounding parts of the town. However, the

exceptional S. porch (photographed below left) is, if anything, even more striking and

scarcely capable of being described as a porch at all, since it assumes

more the character of an entirely separate building which just

happens to be linked to the church's S. doorway. Indeed, it

consists of two discrete parts: (i) a relatively narrow

'linking' section

at the back, sandwiched between two octagonal stair turrets at the point

where it abuts the aisle but splaying out to the south to cover an open

and the Lady Chapel, aligned further to the north alongside St.

Catherine's Chapel, with which it now communicates through an arcade

formed of three narrow bays but which once stood largely apart from the

chancel during an earlier period when St. Catherine's chapel was only a single

bay in length. The aisled nave is six bays long and flanked

alongside the four eastern bays of the N. aisle, by a fourth chapel,

known as the Trinity Chapel, which is divided from the aisle internally

by an elaborate stone screen (illustrated right).

Immediately west of the Trinity Chapel, a porch leads into the

penultimate aisle bay to the west, while the

tower adjoins the west end of the nave in the usual manner and soars up

to a height of 162' (49 m.) (Simon Smith & Derek Barnard, The Parish

Church of St. John the Baptist, Cirencester, Much Wenlock, R.J.L.

Smith & Associates, undated, inside cover), making it visible above the

roof-tops from all the surrounding parts of the town. However, the

exceptional S. porch (photographed below left) is, if anything, even more striking and

scarcely capable of being described as a porch at all, since it assumes

more the character of an entirely separate building which just

happens to be linked to the church's S. doorway. Indeed, it

consists of two discrete parts: (i) a relatively narrow

'linking' section

at the back, sandwiched between two octagonal stair turrets at the point

where it abuts the aisle but splaying out to the south to cover an open east/west passageway; and (ii) the incredible southern

section in front, dated c. 1500 by a series of bequests and reaching up

and out to three storeys high and three asymmetrical bays wide.

Entirely covered in blank tracery and surmounted by pinnacles and

elaborate openwork battlements, it is nevertheless distinguished most

especially by its beautifully proportioned, canted oriel windows

lighting the two upper storeys in each bay. Moreover, lest such a

wealth of display should still be insufficient to demonstrate the

intrinsic independence of the structure, this is given further stress by

the east/west pitch of the roof, where any mere porch would have its

roof pitched north/south. Its side walls are decorated with six

bays of blank tracery, arranged in three tiers, and the entrance

passageway inside, which of necessity runs north/south, is covered by a

fan vault, of which the third bay continues beneath the inner section of

the porch, described above, leading up to the S. aisle door. The

passageway side walls are decorated with more blank tracery and doorways

lead west and east from the outer bay into the main body of the

structure, the former, narrow, four-centred and part of the original

build, and the latter, much larger and either an eighteenth or late

seventeenth century insertion, with a round arch and a keystone.

east/west passageway; and (ii) the incredible southern

section in front, dated c. 1500 by a series of bequests and reaching up

and out to three storeys high and three asymmetrical bays wide.

Entirely covered in blank tracery and surmounted by pinnacles and

elaborate openwork battlements, it is nevertheless distinguished most

especially by its beautifully proportioned, canted oriel windows

lighting the two upper storeys in each bay. Moreover, lest such a

wealth of display should still be insufficient to demonstrate the

intrinsic independence of the structure, this is given further stress by

the east/west pitch of the roof, where any mere porch would have its

roof pitched north/south. Its side walls are decorated with six

bays of blank tracery, arranged in three tiers, and the entrance

passageway inside, which of necessity runs north/south, is covered by a

fan vault, of which the third bay continues beneath the inner section of

the porch, described above, leading up to the S. aisle door. The

passageway side walls are decorated with more blank tracery and doorways

lead west and east from the outer bay into the main body of the

structure, the former, narrow, four-centred and part of the original

build, and the latter, much larger and either an eighteenth or late

seventeenth century insertion, with a round arch and a keystone. either side of a central light featuring two tiers

of reticulation units separated by a latticed supertransom. (See

the glossary for an explanation of these terms.) Internally, the lower

stage is covered by a fan vault. The second

stage is very tall and decorated on all four sides

by blank arcading in two tiers, while the bell-stage -

which, being of more usual height, appears almost squat by comparison -

has three-light, two-centred bell-openings, with supermullioned tracery

above the springing and Somerset tracery below.

either side of a central light featuring two tiers

of reticulation units separated by a latticed supertransom. (See

the glossary for an explanation of these terms.) Internally, the lower

stage is covered by a fan vault. The second

stage is very tall and decorated on all four sides

by blank arcading in two tiers, while the bell-stage -

which, being of more usual height, appears almost squat by comparison -

has three-light, two-centred bell-openings, with supermullioned tracery

above the springing and Somerset tracery below. whose

apex is balanced a seven-light, segmental-pointed window with

supermullioned tracery, which looks out through the east gable, above

the chancel roof. The piers between the bays in the stone screen

dividing the N. aisle from the Trinity Chapel are each formed of four

shafts separated by casements (wide, shallow, hollow chamfers), and the

screen itself has openwork tracery and an ogee entrance arch leading

into the second bay of the chapel from the west. Inside the

Trinity Chapel, the E. wall is decorated with crocketed

canopied niches supported by angels beneath the pedestals, of which

four are now empty and the central one holds a statue of the Risen

Christ.

whose

apex is balanced a seven-light, segmental-pointed window with

supermullioned tracery, which looks out through the east gable, above

the chancel roof. The piers between the bays in the stone screen

dividing the N. aisle from the Trinity Chapel are each formed of four

shafts separated by casements (wide, shallow, hollow chamfers), and the

screen itself has openwork tracery and an ogee entrance arch leading

into the second bay of the chapel from the west. Inside the

Trinity Chapel, the E. wall is decorated with crocketed

canopied niches supported by angels beneath the pedestals, of which

four are now empty and the central one holds a statue of the Risen

Christ. which

notes in the church ascribe to the memory of George Monox (d. 1638) and

his wife, and suggest may be the work of the sculptor, Samuel Baldwin of

Stroud (d. 1645). Finally, six later (and smaller) monuments in

the church which can definitely be ascribed to their makers are three by

Joseph Franklin (fl. 1789-1850), commemorating Jonathan Skinn (d. 1791),

William Hewer (d. 1792) and John Cripps (d. 1793), two by John Charles

Felix Rossi (1762-1839), dedicated to Maria Master (d. 1819) and Thomas

Master (d. 1823), and one featuring two busts by Joseph Nollekens

(1737-1823), dedicated to the Earl (d. 1775) and Countess Bathurst (Rupert

Gunnis, Dictionary

of British Sculptors: 1660-1851, London, The Abbey

Library, 1951, p. 277) and unfortunately cut down.

which

notes in the church ascribe to the memory of George Monox (d. 1638) and

his wife, and suggest may be the work of the sculptor, Samuel Baldwin of

Stroud (d. 1645). Finally, six later (and smaller) monuments in

the church which can definitely be ascribed to their makers are three by

Joseph Franklin (fl. 1789-1850), commemorating Jonathan Skinn (d. 1791),

William Hewer (d. 1792) and John Cripps (d. 1793), two by John Charles

Felix Rossi (1762-1839), dedicated to Maria Master (d. 1819) and Thomas

Master (d. 1823), and one featuring two busts by Joseph Nollekens

(1737-1823), dedicated to the Earl (d. 1775) and Countess Bathurst (Rupert

Gunnis, Dictionary

of British Sculptors: 1660-1851, London, The Abbey

Library, 1951, p. 277) and unfortunately cut down.