|

English Church Architecture.

FOTHERINGHAY, St. Mary & All Saints (TL 060 932), NORTHAMPTONSHIRE. (Bedrock: Middle Jurassic, Upper Estuarine Series.)

An outstanding Perpendicular church, famous especially for its tower, surmounted by a tall lantern.

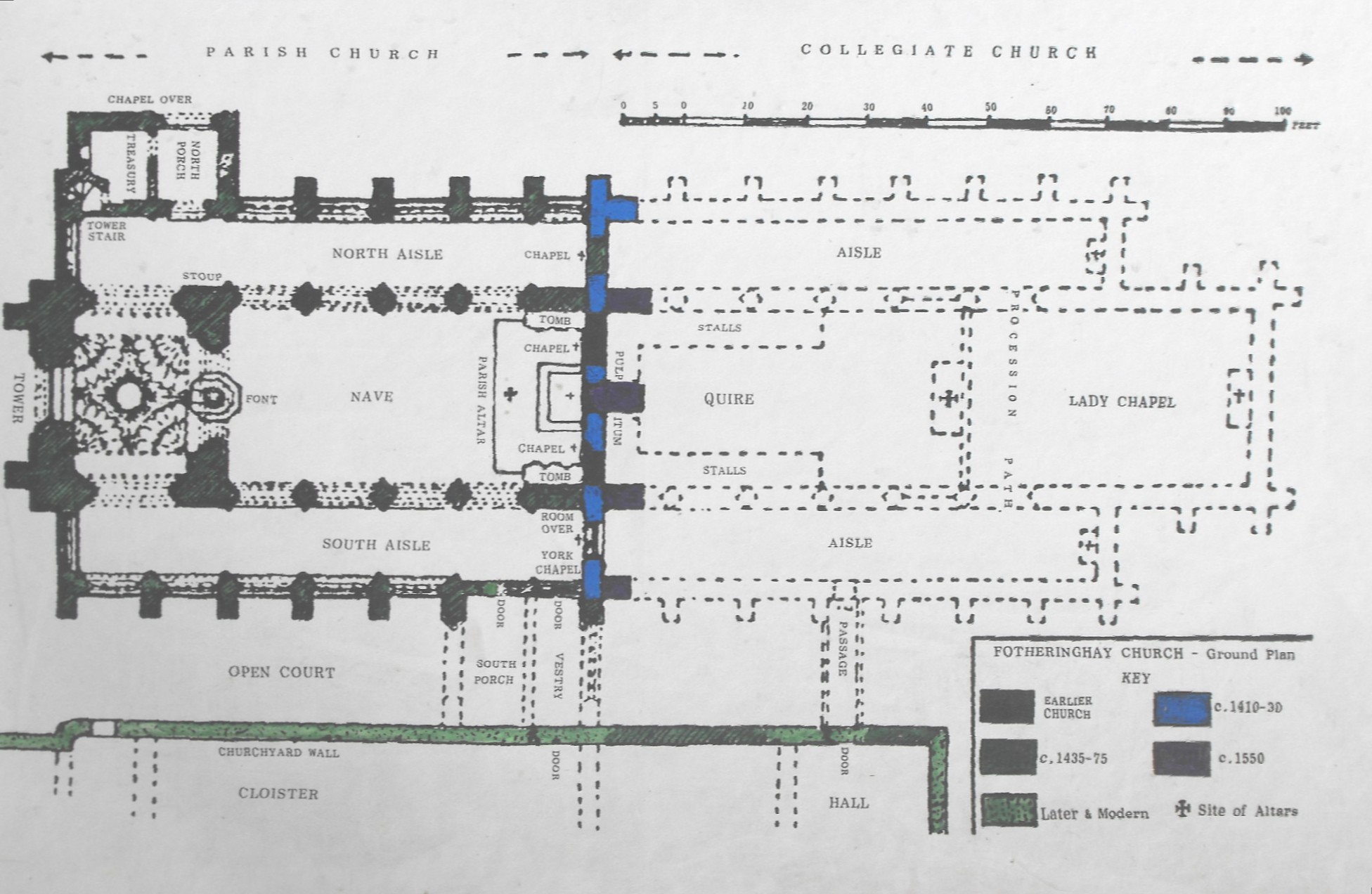

This impressive building is, notwithstanding, less than half what it was, for the aisled quire and Lady Chapel, erected after the foundation of a college of priests in 1411 and demolished in 1573, briefly extended twice as far eastward again. (Compare the photograph above with that of the model of the church c. 1500 at the foot of this page.) The church today consists of a massive W. tower with a tall surmounting octagonal lantern and an aisled nave with a very large, two-storeyed N. porch, and was begun c. 1434 - a date which explains some of the oddities at the church's E. end (see the photograph below left), since when the quire was erected a couple of decades beforehand, the five-light window high up in what has since become the nave E. wall, and the relict windows (only visible outside) now open to the sky above the aisles, looked out westwards above the earlier low, aisled Norman nave. (N.B. Pevsner, writing in the 'Northamptonshire' volume of The Buildings of England in 1973 (Harmondsworth, Penguin, p. 220), wrongly assumed the quire was formerly lower than the nave and that these windows had looked out eastward above the quire and its aisles - the reverse of the actual case.) The monastic cloister lay to the south, linked - after the rebuilding of the nave and aisles was complete - to the church by a short passage, inaccurately described on the large church plan drawn on card, inside the church, as a 'S. porch'. (See the photograph second below.) It follows that everything that survives is Perpendicular in style, and the work is particularly interesting since the master masons are known: William Horewode for the principal structure of the nave and tower, with whom a contract exists dated 24th September 1434, agreeing a price for the work of £300; and Henry Semark for the fan vault beneath the tower, dated 1529, when Semark was aged about seventy (John Harvey, English Mediaeval Architects - a Biographical Dictionary down to 1550, Gloucester, Alan Sutton, 1987, p. 394). The demolished eastern parts of the building were designed by Stephen Lote, whose influence can probably still be seen, albeit at second hand, in Horewode's aisled nave, believed to have been erected with the intention of matching it. The cursory church guide (anon. 2009) suggests that the gargoyle at the eastern end of the church to the north, is a depiction of William Horewode. If so, this would be a very unusual but not unique example of a mediaeval mason being immortalized in stone: Henry Yevele, court mason in turn to Edward III and Richard II, who is believed to have designed, among other important works, the cloister at Canterbury Cathedral, can probably be seen on a vault boss there.

A description of the present church must obviously follow. The very broad tower is supported by clasping buttresses and rises in two stages, the second recessed, to four-light, transomed bell-openings and large octagonal corner pinnacles, lit by an eight-light W. window below with lights subarcuated in fours and through-reticulation (see the photograph above right, taken from the northwest), but unusual though the dimensions of this work are, its chief function is surely to draw the eye upwards to the wonderful embattled lantern, with pinnacles at the angles and three-light transomed windows that occupy almost the whole of their respective sides. Best viewed across fields from the road bridge over the River Nene to the south (as in the photograph at the top of the page), this forms an exceptional composition.

The aisles embrace the tower and then continue for four further bays eastward alongside the nave, lit by tall four-light windows with strong mullions, outer lights subarcuated above inverted daggers, quatrefoils above supermullioned tracery over the central lights, and cinquefoil cusping to both the principal lights and the sub-lights. (See the glossary for an explanation of these terms.) The bays are separated by buttresses topped by crocketed pinnacles with blank Y-tracery on the sides. The nave clerestory is supported above the aisles by flying buttresses, though whether for structural reasons due to its considerable height or simply for appearance's sake, is difficult to say. The easternmost bay of the S. aisle has a solid S. wall marked by an assortment of blocked openings, showing where the connecting passage once joined it to the cloister. The heavily constructed N. porch is as large and sturdy as it is because previously it once also contained the church's treasury, which was the function of the little room on the ground floor, west of the entrance passage, accessed internally through the door from the aisle. The upper storey provided a residence for the sexton, intended to be 'permanently occupied [in order that the] sexton could observe security from the high window on the right' (church guide).

After all this, the church interior is a little disappointing. The best individual feature is the very fine fan vault beneath the tower, already mentioned, rising from figure corbels at the angles and now with a modern painted panel in the centre where there was originally an opening for the passage of bell-ropes. (See above.) The N. and S. arches between the tower and aisles are separate from the aisle arcades and carry a complex series of mouldings above semicircular shafts. The E. arch from the tower to the nave is taller but otherwise similar and the four-bay nave arcades (seen below left in the internal photograph of the church, viewed from the west) follow the same general form and have capitals to the semicircular shafts towards the openings, and narrower semicircular shafts rising up on the side towards the nave, between the bays, to meet a string course below the clerestory windows.

Furnishings in the church include the very elaborate pulpit and tester (above right), believed to have been given to the church by Edward IV (reigned 1461-70 & 1471-83) (church guide), although, in truth, it is probably more striking for its 1960s paintwork in greens, blues and browns than for its carpentry, fine though that is. The reredos is actually a Georgian Decalogue on which is written, as was usual, the Apostles' Creed, the Ten Commandments and the Lord's Prayer. The box pews in the nave are early nineteenth century work. The church contains no monuments of note apart from two distinctly inscrutable ones, without figures, set either side of the sanctuary, which the church guide records as having been ordered to be placed here by Queen Elizabeth I after her visit to Fotheringhay in 1566. Apparently they commemorate: (i) on the right, Edward, second Duke of York, who was responsible for founding the college of priest's four years before he was killed at Agincourt (in 1415); and (ii), on the left, Edward's nephew, Richard, the third Duke of York, and Cecily Neville, his wife (d. 1460 and 1495 respectively).

|