This

so-called chapel (for it was built as a private chapel for Clumber

House) is, in reality, a soaring masterpiece of a church by George Frederick

Bodley, erected in 1886-9 at a cost of

£40,000 (about 3.3 million pounds

today). 'Bodley brought Gothic to a state of refinement that it

had probably never reached before', wrote

Basil F.L. Clarke (Church Builders of the Nineteenth Century,

London. SPCK, 1938, p. 212), and we can recognise some of the artist's fingerprints

here, by comparing this building with St. Mary's, Eccleston (West

Cheshire & Chester):

both adopt a Second Pointed (Decorated) style, modified by elements drawn

from Perpendicular work; both have their windows set very high up,

giving the buildings a somewhat fortress-like appearance; both are fully

vaulted within; both employ stone figures in elaborate canopied

niches as an important element of their decorative

schemes. However, another close relationship between these two

buildings concerns their use of New Red Sandstone from the Triassic

Bunter Pebble Beds as their principal building material - a

situation arising purely from the fact that both

of these buildings sit on outcrops of this stone on opposite sides

of the Pennines, albeit that, perversely, the red sandstone used at Clumber was

actually brought across the Pennines from Runcorn, in a blatant

case of 'carrying coals to Newcastle'. It is used exclusively

inside the building, while outside it is employed for the crossing tower from the bell-stage upwards and

for dressings everywhere else, where it forms a striking contrast with a

truly local stone - the white magnesian Steetley Stone of Permian age

from Whitwell, just across the Derbyshire border, which had been

preserved from the former, demolished chapel, and which the patron, the

7th Duke of Newcastle, insisted should be re-used as far as possible

(Michael Hall, George Frederick Bodley, New Haven & London, Yale

University Press, 2014, p. 289). Perhaps the most obvious differences between St.

Mary's, Clumber and St. Mary's, Eccleston, lie in their plans and the

forms of their towers, for

the present church is cruciform and has an angle-buttressed tower

crowned by a magnificent octagonal corona and spire (shown below left),

the former supported by flying buttresses springing across from

crocketed pinnacles

at the tower corners, and the latter rising through the corona to a

total height of 180' (55 m.) above the ground, producing a

building 30% taller than it is long.

This

so-called chapel (for it was built as a private chapel for Clumber

House) is, in reality, a soaring masterpiece of a church by George Frederick

Bodley, erected in 1886-9 at a cost of

£40,000 (about 3.3 million pounds

today). 'Bodley brought Gothic to a state of refinement that it

had probably never reached before', wrote

Basil F.L. Clarke (Church Builders of the Nineteenth Century,

London. SPCK, 1938, p. 212), and we can recognise some of the artist's fingerprints

here, by comparing this building with St. Mary's, Eccleston (West

Cheshire & Chester):

both adopt a Second Pointed (Decorated) style, modified by elements drawn

from Perpendicular work; both have their windows set very high up,

giving the buildings a somewhat fortress-like appearance; both are fully

vaulted within; both employ stone figures in elaborate canopied

niches as an important element of their decorative

schemes. However, another close relationship between these two

buildings concerns their use of New Red Sandstone from the Triassic

Bunter Pebble Beds as their principal building material - a

situation arising purely from the fact that both

of these buildings sit on outcrops of this stone on opposite sides

of the Pennines, albeit that, perversely, the red sandstone used at Clumber was

actually brought across the Pennines from Runcorn, in a blatant

case of 'carrying coals to Newcastle'. It is used exclusively

inside the building, while outside it is employed for the crossing tower from the bell-stage upwards and

for dressings everywhere else, where it forms a striking contrast with a

truly local stone - the white magnesian Steetley Stone of Permian age

from Whitwell, just across the Derbyshire border, which had been

preserved from the former, demolished chapel, and which the patron, the

7th Duke of Newcastle, insisted should be re-used as far as possible

(Michael Hall, George Frederick Bodley, New Haven & London, Yale

University Press, 2014, p. 289). Perhaps the most obvious differences between St.

Mary's, Clumber and St. Mary's, Eccleston, lie in their plans and the

forms of their towers, for

the present church is cruciform and has an angle-buttressed tower

crowned by a magnificent octagonal corona and spire (shown below left),

the former supported by flying buttresses springing across from

crocketed pinnacles

at the tower corners, and the latter rising through the corona to a

total height of 180' (55 m.) above the ground, producing a

building 30% taller than it is long.

It would be

excessively tedious, therefore, after these opening remarks, to attempt a comprehensive description of so rich

and elaborate a building, but the mere enumeration of its component

parts will provide some impression of its complexities for the

chapel

consists of a four-bay chancel with a three-bay chapel to the south and

a balancing organ chamber and vestry to the north, the crossing tower

and spire already mentioned, N. and S. transepts, a four-bay nave, and

little annexes in the re-entrants between the nave and the transepts,

more conspicuous inside than out, forming a baptistry to the north and

another small chapel opposite. Windows to the building are mostly

two-light in the nave and S. chapel, with cruciform lobing set

vertically in the former and falchion tracery in the latter (see the

glossary for an explanation of these terms), and

three-light with variant forms of reticulated tracery in the chancel

clerestory. The chancel is slightly longer and taller than the

nave but the transepts are lower than either, yet still more than twice

the height of the annexes. There are niches containing statuettes

either side of the five-light chancel E. window with its excellent

curvilinear tracery, the three-light nave W. window, and the three-light

S. transept S. window. The nave is faced entirely with Steetley

Stone below the windows but banded with red sandstone above, while the

position is reversed, east of the crossing, so that the S chapel walls

are banded while the chancel clerestory walls are not. The church

has no porch and entry is gained through the nave W. doorway, composed

of three orders bearing wave mouldings and a frieze of leaf carving

around these.

It would be

excessively tedious, therefore, after these opening remarks, to attempt a comprehensive description of so rich

and elaborate a building, but the mere enumeration of its component

parts will provide some impression of its complexities for the

chapel

consists of a four-bay chancel with a three-bay chapel to the south and

a balancing organ chamber and vestry to the north, the crossing tower

and spire already mentioned, N. and S. transepts, a four-bay nave, and

little annexes in the re-entrants between the nave and the transepts,

more conspicuous inside than out, forming a baptistry to the north and

another small chapel opposite. Windows to the building are mostly

two-light in the nave and S. chapel, with cruciform lobing set

vertically in the former and falchion tracery in the latter (see the

glossary for an explanation of these terms), and

three-light with variant forms of reticulated tracery in the chancel

clerestory. The chancel is slightly longer and taller than the

nave but the transepts are lower than either, yet still more than twice

the height of the annexes. There are niches containing statuettes

either side of the five-light chancel E. window with its excellent

curvilinear tracery, the three-light nave W. window, and the three-light

S. transept S. window. The nave is faced entirely with Steetley

Stone below the windows but banded with red sandstone above, while the

position is reversed, east of the crossing, so that the S chapel walls

are banded while the chancel clerestory walls are not. The church

has no porch and entry is gained through the nave W. doorway, composed

of three orders bearing wave mouldings and a frieze of leaf carving

around these.

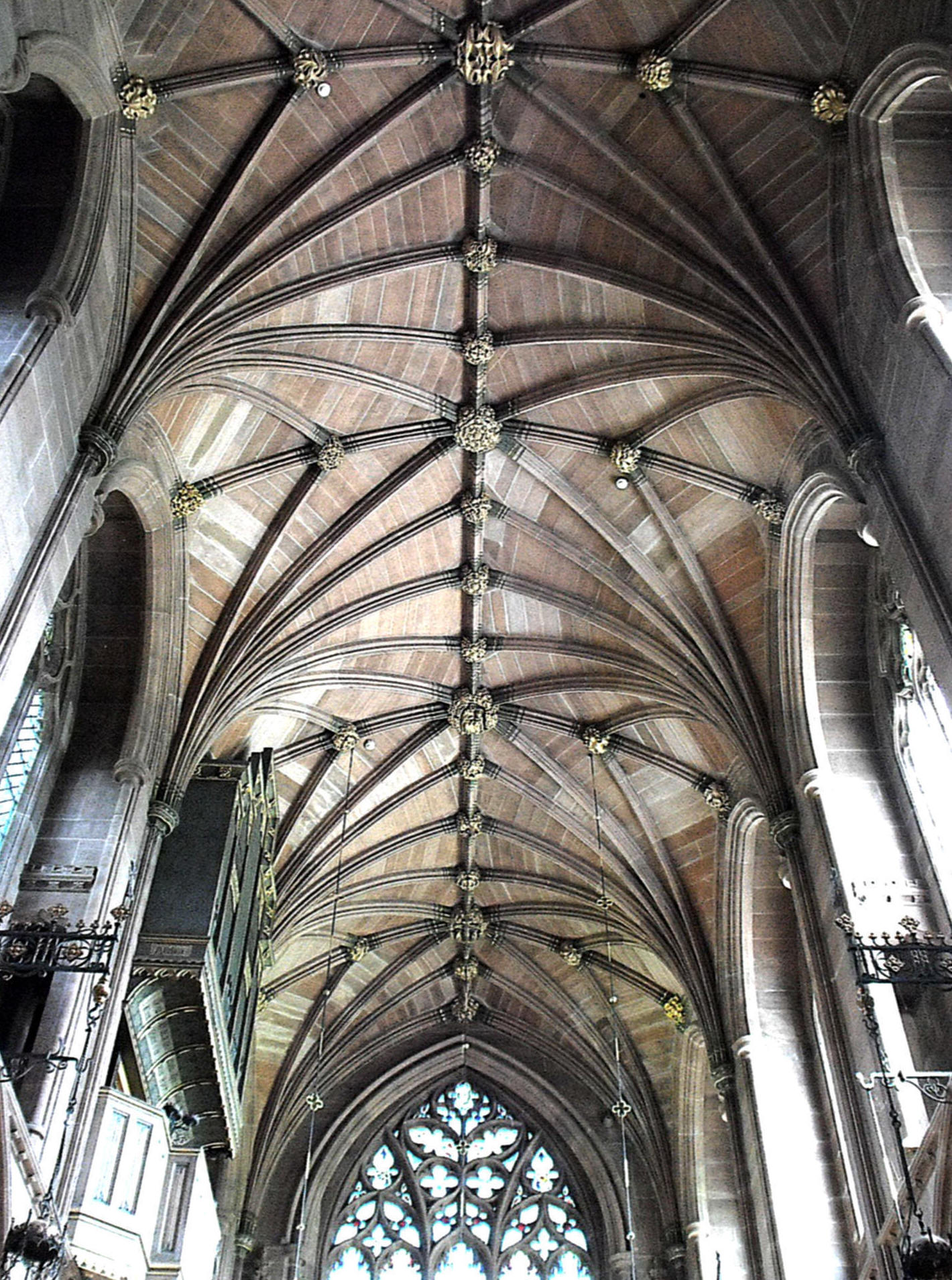

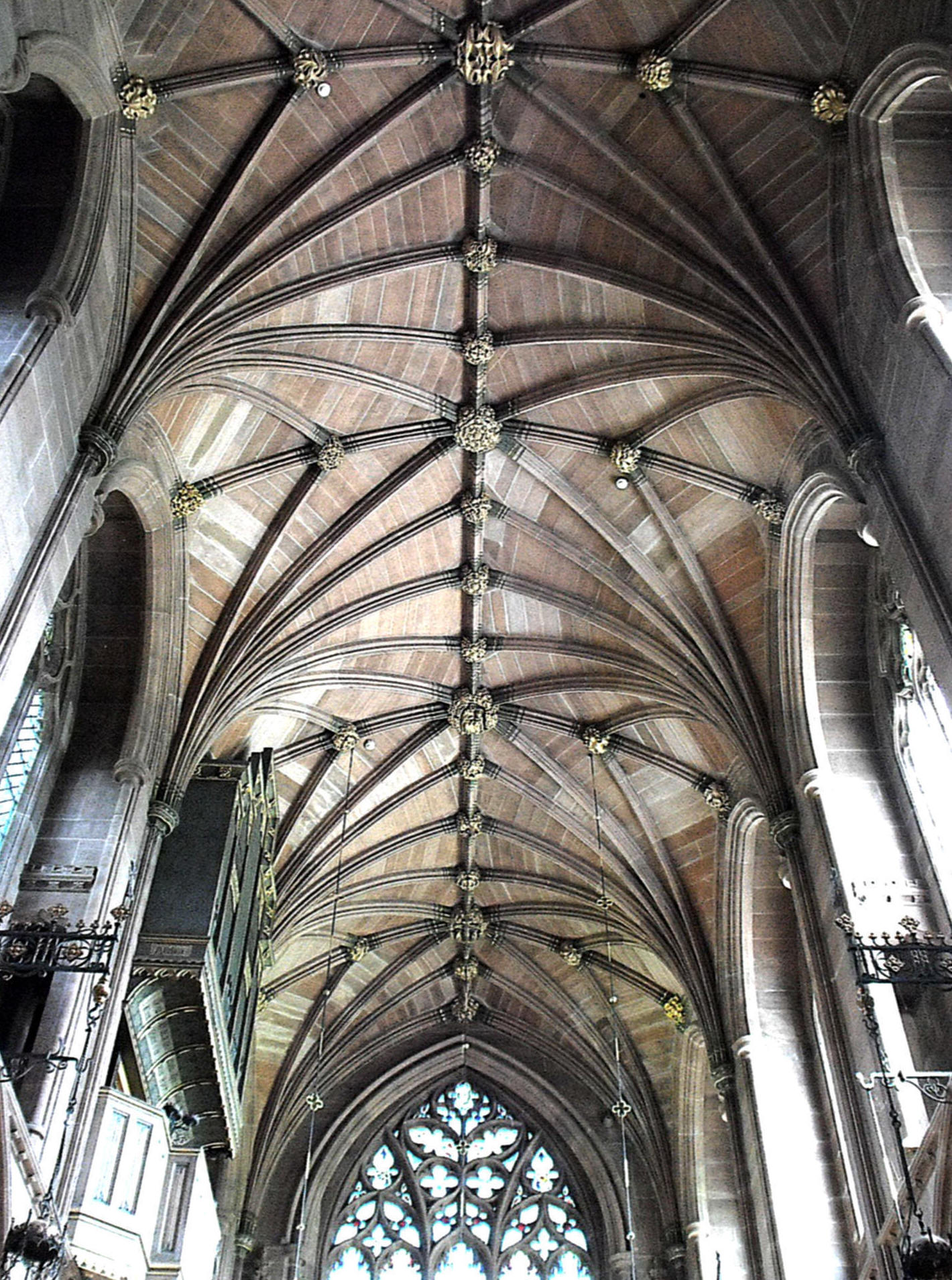

Inside the building, it is chiefly the vaulting schemes that portray the

approaching ecclesiastical climax as one passes from the nave with its

sexpartite ribbed vault, beneath the crossing with its octopartite

vault with the usual central hole to allow the passage of the

bell-ropes, finally to arrive in the chancel with its

tierceron vault

(shown left) or, even more

especially, in the ornate S. chapel, with its lierne vault (illustrated below right).

Inside the building, it is chiefly the vaulting schemes that portray the

approaching ecclesiastical climax as one passes from the nave with its

sexpartite ribbed vault, beneath the crossing with its octopartite

vault with the usual central hole to allow the passage of the

bell-ropes, finally to arrive in the chancel with its

tierceron vault

(shown left) or, even more

especially, in the ornate S. chapel, with its lierne vault (illustrated below right).

The nave walls are faced along their three

western bays with deeply-set blank arches carrying a wave moulding and a

hollow filled at intervals with carved roses above an order of engaged

shafts, but the easternmost bays are cut through by the arches to the

transept annexes, formed of a series of narrow mouldings either side of

wide soffits decorated with vine leaf carving in relief.

Passageways at window level, pass east/west through the thickness of the

nave walls, beneath depressed ogee arches, as they do also behind the

chancel clerestory. The nave vault rises from (though hardly

appears to be resting on) groups of three narrow bowtells that run up

between the bays, and in like manner, the tall crossing arches

towards the nave and chancel, also appear to rely on the same flimsy

support. The arches towards the transepts die into the jambs.

The

most impressive parts of the church, however, are the chancel and S.

chapel. Three-bay arcades filled with stone screens run down each side of the chancel, with open tracery on the

south side providing a view into the chapel, and blank tracery on the

north side, providing privacy for the vestry. The arcades are

formed of a complex series of mouldings above three orders of shafts,

with the outer pair cut from 'local' New Red sandstone, and the

one between, from imported black marble (as seen right). The screens fill the

arches to the height of the springing and feature reticulated tracery

above ogee-pointed lights and plain dados. The arch to the

S. chapel from the transept is formed of three orders, springing from

responds with two orders of shafts decorated with carved roses around

the capitals.

Finally, furnishings to the

building are almost inevitably eclipsed by all this excellent stonework

and, besides, were mostly designed after Bodley was finally dismissed by

Newcastle for over-running his account (ibid., p. 281). The

wooden screen between the crossing and the chancel is too big not to

mention, however, and the rood above is also interesting for it was designed by

the Reverend

Ernest Geldhart, whose carpentry and decorative schemes are generally

found in Essex. Here, he was responsible for the tall

font cover and the delicately carved choir stalls of walnut and cedar

wood.

This

so-called chapel (for it was built as a private chapel for Clumber

House) is, in reality, a soaring masterpiece of a church by George Frederick

Bodley, erected in 1886-9 at a cost of

This

so-called chapel (for it was built as a private chapel for Clumber

House) is, in reality, a soaring masterpiece of a church by George Frederick

Bodley, erected in 1886-9 at a cost of

It would be

excessively tedious, therefore, after these opening remarks, to attempt a comprehensive description of so rich

and elaborate a building, but the mere enumeration of its component

parts will provide some impression of its complexities for the

chapel

consists of a four-bay chancel with a three-bay chapel to the south and

a balancing organ chamber and vestry to the north, the crossing tower

and spire already mentioned, N. and S. transepts, a four-bay nave, and

little annexes in the re-entrants between the nave and the transepts,

more conspicuous inside than out, forming a baptistry to the north and

another small chapel opposite. Windows to the building are mostly

two-light in the nave and S. chapel, with cruciform lobing set

vertically in the former and falchion tracery in the latter (see the

glossary for an explanation of these terms), and

three-light with variant forms of reticulated tracery in the chancel

clerestory. The chancel is slightly longer and taller than the

nave but the transepts are lower than either, yet still more than twice

the height of the annexes. There are niches containing statuettes

either side of the five-light chancel E. window with its excellent

curvilinear tracery, the three-light nave W. window, and the three-light

S. transept S. window. The nave is faced entirely with Steetley

Stone below the windows but banded with red sandstone above, while the

position is reversed, east of the crossing, so that the S chapel walls

are banded while the chancel clerestory walls are not. The church

has no porch and entry is gained through the nave W. doorway, composed

of three orders bearing wave mouldings and a frieze of leaf carving

around these.

It would be

excessively tedious, therefore, after these opening remarks, to attempt a comprehensive description of so rich

and elaborate a building, but the mere enumeration of its component

parts will provide some impression of its complexities for the

chapel

consists of a four-bay chancel with a three-bay chapel to the south and

a balancing organ chamber and vestry to the north, the crossing tower

and spire already mentioned, N. and S. transepts, a four-bay nave, and

little annexes in the re-entrants between the nave and the transepts,

more conspicuous inside than out, forming a baptistry to the north and

another small chapel opposite. Windows to the building are mostly

two-light in the nave and S. chapel, with cruciform lobing set

vertically in the former and falchion tracery in the latter (see the

glossary for an explanation of these terms), and

three-light with variant forms of reticulated tracery in the chancel

clerestory. The chancel is slightly longer and taller than the

nave but the transepts are lower than either, yet still more than twice

the height of the annexes. There are niches containing statuettes

either side of the five-light chancel E. window with its excellent

curvilinear tracery, the three-light nave W. window, and the three-light

S. transept S. window. The nave is faced entirely with Steetley

Stone below the windows but banded with red sandstone above, while the

position is reversed, east of the crossing, so that the S chapel walls

are banded while the chancel clerestory walls are not. The church

has no porch and entry is gained through the nave W. doorway, composed

of three orders bearing wave mouldings and a frieze of leaf carving

around these. Inside the building, it is chiefly the vaulting schemes that portray the

approaching ecclesiastical climax as one passes from the nave with its

sexpartite ribbed vault, beneath the crossing with its octopartite

vault with the usual central hole to allow the passage of the

bell-ropes, finally to arrive in the chancel with its

tierceron vault

(shown left) or, even more

especially, in the ornate S. chapel, with its lierne vault (illustrated below right).

Inside the building, it is chiefly the vaulting schemes that portray the

approaching ecclesiastical climax as one passes from the nave with its

sexpartite ribbed vault, beneath the crossing with its octopartite

vault with the usual central hole to allow the passage of the

bell-ropes, finally to arrive in the chancel with its

tierceron vault

(shown left) or, even more

especially, in the ornate S. chapel, with its lierne vault (illustrated below right).