This attractive village is rightly famous as the site of

possibly the most important quarry in mediaeval England, from whence was

dug the incomparable Middle Jurassic Barnack rag. Barnack lies

between two great fenland rivers, the Welland and the Nene, which

approach within one mile to the north and three miles to the south

respectively and along which stone could be transported either further

inland or out to The Wash, around the coast, and, perhaps, back up other

rivers like the Yare. Thus Norwich, Peterborough and Ely Cathedrals

were all largely built of this material, and the quarry, though once

covering much of the present village, was almost worked out by the end

of the fifteenth century, as a result of which substitutes have had to

be found for subsequent

restoration work from deposits of similar

age and lithology in neighbouring places which have themselves often

become synonymous with high quality building stone, such as Ketton in

Rutland and Ancaster in Lincolnshire. Today, a part of the

erstwhile Barnack quarry, known for obvious reasons as the 'Hills and

Holes', is preserved as a National Nature Reserve, over whose hummocky

terrain, pasque flowers bloom in May and marbled white and chalkhill blue

butterflies flit in July and August. (See the photographs at the foot of the page.)

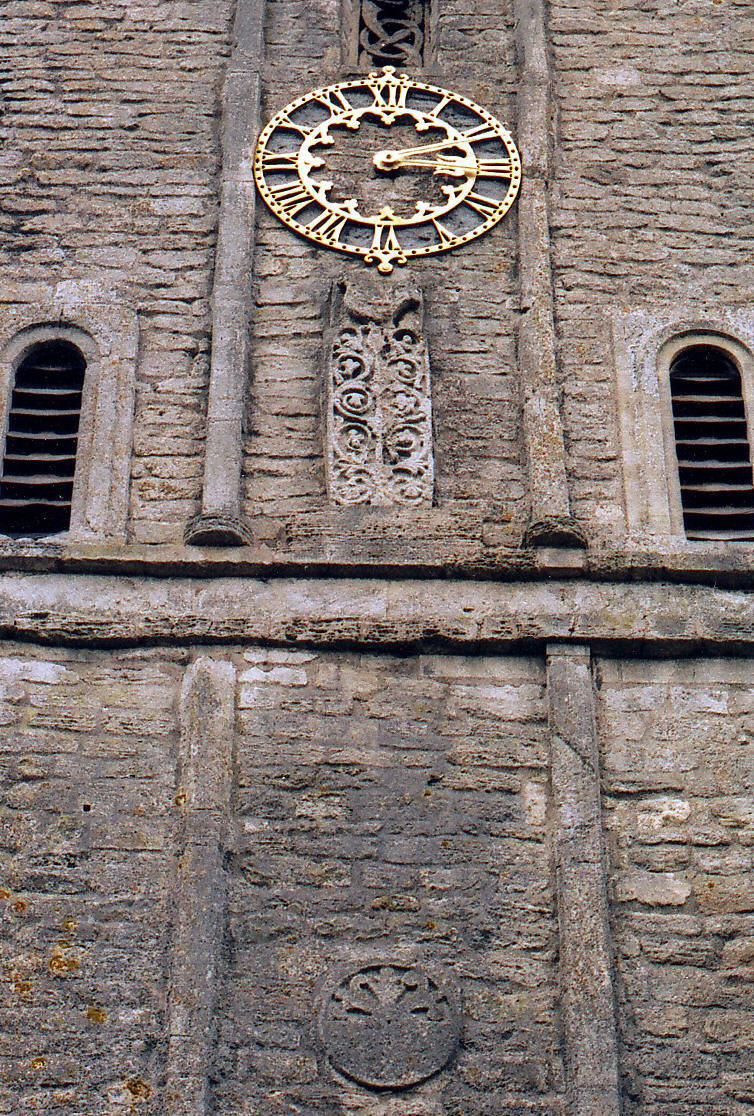

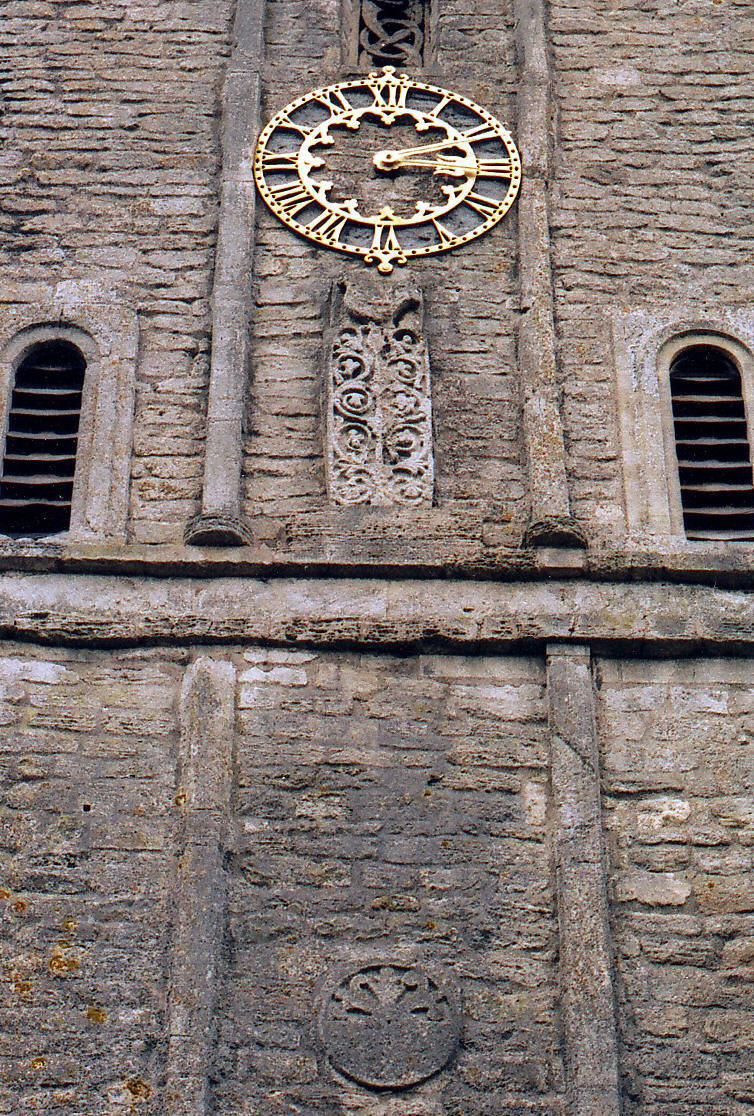

The important church of St. John the Baptist, which is

built entirely of Barnack stone, owes its particular fame, however,

principally to the W. tower, formed of two square, Saxon stages,

dating from c. 1000, on top of which an octagonal bell-stage was added

in the early thirteenth century, with tall

octagonal pinnacles rising from broaches and a short surmounting spire

which

is probably the

earliest broach spire England.

The two Saxon stages have characteristic long-and-short work at the

angles (quoins set alternately vertically and horizontally) and are constructed of

roughly-coursed ragstone that contrasts with the finely cut ashlar used

in the church elsewhere. The four walls are each divided into four

narrow sections by projecting lesenes and are pierced by an

assortment of round-headed and triangular-headed openings, some now

blocked, including a S. doorway that gives direct access to the

tower. A carved decorative panel

at the base of the upper stage

to the north and south (of which the latter is shown below), feature

interlacing and what appears to be a cockerel, and the S. wall

also displays a smaller, circular panel at the top of the lower stage,

considered to be the remains of a sundial. Inside the building,

the heavy, round-headed Saxon tower arch is formed of two unmoulded

orders, springing from wide rectangular jambs with imposts like giant

stone sandwiches with the 'filling' recessed in the centre. (See

the N. jamb

below.) These are similar to the

tower arch imposts at St. Beneítís church, Cambridge, and suggest, as

there, an imperfect understanding on the part of the builders of the

structural function of this feature. The quadripartite ribbed

feature

interlacing and what appears to be a cockerel, and the S. wall

also displays a smaller, circular panel at the top of the lower stage,

considered to be the remains of a sundial. Inside the building,

the heavy, round-headed Saxon tower arch is formed of two unmoulded

orders, springing from wide rectangular jambs with imposts like giant

stone sandwiches with the 'filling' recessed in the centre. (See

the N. jamb

below.) These are similar to the

tower arch imposts at St. Beneítís church, Cambridge, and suggest, as

there, an imperfect understanding on the part of the builders of the

structural function of this feature. The quadripartite ribbed

vault underneath the tower, with a round central

hole for the bell-ropes

to pass through, was inserted to provide extra support when the

bell-stage was added. This has two-light, round-arched bell-openings,

with central colonnettes supporting Y-tracery and three orders of

colonnettes at the sides with dog-tooth moulding alongside those.

The late Philip G.M. Dickinson, in his admirable guide to the church,

ascribed this to c. 1200, presumably on the strength of the round

arches, but that may be a little too early (Barnack Church,

revised J. Martin Goodwin, 1990, p. 22).

vault underneath the tower, with a round central

hole for the bell-ropes

to pass through, was inserted to provide extra support when the

bell-stage was added. This has two-light, round-arched bell-openings,

with central colonnettes supporting Y-tracery and three orders of

colonnettes at the sides with dog-tooth moulding alongside those.

The late Philip G.M. Dickinson, in his admirable guide to the church,

ascribed this to c. 1200, presumably on the strength of the round

arches, but that may be a little too early (Barnack Church,

revised J. Martin Goodwin, 1990, p. 22).

The

rest of the building consists of an aisled nave with a S. porch, and a

chancel with a large S. chapel and a shorter N. chapel and adjoining

vestry, beyond which the sanctuary projects one further bay to the east.

The earliest feature anywhere here may be the

arch between the chancel and N. chapel (now the organ chamber), which is

round-headed and springs from semicircular responds with capitals

reminiscent of waterleaf. This could date from c. 1180

onwards, although it appears to have been restored. The three-bay

aisle arcades were considered by Dickinson to date from c. 1190 in the

case of the N. arcade and c. 1200 in the case of its southern

counterpart (Barnack Church, p. 10), but it is a brave soul that

attempts such precise dating as this since the stylistic differences between them, though

significant, are sufficiently close to one another in the evolution of

architectural style as to be equally explicable by the involvement of different masons. Both arcades are round-arched, but the

northern one is supported on relatively slim, circular piers with

'remarkable foliated capitals of unusual design', from which rise arches

bearing chevron and keeled rolls - and so if this is the more

conservative piece of work in some respects, it is by no means

a merely conventional one. The S. arcade (illustrated left)

is supported on fairly broad piers, formed from the clustering of eight

unequal semicircular shafts, and has capitals that look forward to stiff

leaf and arches bearing a series of unequal rolls. However,

whatever the precise date of this work may be, it is probably the same

as the date of the porch and the S. aisle walls to the west, while the

date of the N. arcade is probably that of the N. aisle walls (although

not the windows in either case). The S. porch (seen below right)

has no side windows but the outer doorway is adorned with three orders of

shafts with stiff leaf capitals and the side walls are furnished

internally with four-bay blank arcades supported on single colonnettes,

above which is what Dickinson aptly described as 'a peculiar

domical rib-vaulted ceiling which

The

rest of the building consists of an aisled nave with a S. porch, and a

chancel with a large S. chapel and a shorter N. chapel and adjoining

vestry, beyond which the sanctuary projects one further bay to the east.

The earliest feature anywhere here may be the

arch between the chancel and N. chapel (now the organ chamber), which is

round-headed and springs from semicircular responds with capitals

reminiscent of waterleaf. This could date from c. 1180

onwards, although it appears to have been restored. The three-bay

aisle arcades were considered by Dickinson to date from c. 1190 in the

case of the N. arcade and c. 1200 in the case of its southern

counterpart (Barnack Church, p. 10), but it is a brave soul that

attempts such precise dating as this since the stylistic differences between them, though

significant, are sufficiently close to one another in the evolution of

architectural style as to be equally explicable by the involvement of different masons. Both arcades are round-arched, but the

northern one is supported on relatively slim, circular piers with

'remarkable foliated capitals of unusual design', from which rise arches

bearing chevron and keeled rolls - and so if this is the more

conservative piece of work in some respects, it is by no means

a merely conventional one. The S. arcade (illustrated left)

is supported on fairly broad piers, formed from the clustering of eight

unequal semicircular shafts, and has capitals that look forward to stiff

leaf and arches bearing a series of unequal rolls. However,

whatever the precise date of this work may be, it is probably the same

as the date of the porch and the S. aisle walls to the west, while the

date of the N. arcade is probably that of the N. aisle walls (although

not the windows in either case). The S. porch (seen below right)

has no side windows but the outer doorway is adorned with three orders of

shafts with stiff leaf capitals and the side walls are furnished

internally with four-bay blank arcades supported on single colonnettes,

above which is what Dickinson aptly described as 'a peculiar

domical rib-vaulted ceiling which

seems

to have been more than its builder was able to cope with successfully'

(Barnack Church, p. 15). The two-light

N. aisle windows appear to have been inserted c. 1300 for they have side

shafts internally still of thirteenth century appearance, yet also

cusped Y-tracery with trefoils in the heads of the lights and inverted

daggers in the eyelets; the S. aisle windows west of the porch

take on a more developed Decorated appearance by including ogees,

which suggests they postdate c.1315, but the segmental-arched windows in

the S. aisle, east of the porch, may be a little later still, in spite

of being otherwise similar to the N. aisle windows, having apparently

been constructed when this part of the aisle was widened and given the

line of ballflower ornament that runs beneath the parapet.

In any event, also in Decorated times, the N. vestry was added at the E.

end of the N.

chapel and the present N. and S. windows were inserted in the sanctuary

(i.e. where the chancel projects beyond the S. chapel and N. vestry),

of which that in the S. wall is similar to

those in the aisle west of the porch. The exceptional

five-light E. window to the chancel

(below), dating,

perhaps,

from c. 1300, displays what are possibly the unique features of

mullions

seems

to have been more than its builder was able to cope with successfully'

(Barnack Church, p. 15). The two-light

N. aisle windows appear to have been inserted c. 1300 for they have side

shafts internally still of thirteenth century appearance, yet also

cusped Y-tracery with trefoils in the heads of the lights and inverted

daggers in the eyelets; the S. aisle windows west of the porch

take on a more developed Decorated appearance by including ogees,

which suggests they postdate c.1315, but the segmental-arched windows in

the S. aisle, east of the porch, may be a little later still, in spite

of being otherwise similar to the N. aisle windows, having apparently

been constructed when this part of the aisle was widened and given the

line of ballflower ornament that runs beneath the parapet.

In any event, also in Decorated times, the N. vestry was added at the E.

end of the N.

chapel and the present N. and S. windows were inserted in the sanctuary

(i.e. where the chancel projects beyond the S. chapel and N. vestry),

of which that in the S. wall is similar to

those in the aisle west of the porch. The exceptional

five-light E. window to the chancel

(below), dating,

perhaps,

from c. 1300, displays what are possibly the unique features of

mullions terminating in tiny finials between the lights and

trefoil-cusped crocketed gables topped by larger finials within.

The S. chapel (below right) is an addition of the late fifteenth or

early sixteenth century, and consists of two unequal bays, the western

bay lit to the south by two conjoined, two-light windows, and the

eastern bay, by a similar but three-light window to the south and

another three-light window to the east. However, the chapel

depends for its effect not on its fenestration but on

terminating in tiny finials between the lights and

trefoil-cusped crocketed gables topped by larger finials within.

The S. chapel (below right) is an addition of the late fifteenth or

early sixteenth century, and consists of two unequal bays, the western

bay lit to the south by two conjoined, two-light windows, and the

eastern bay, by a similar but three-light window to the south and

another three-light window to the east. However, the chapel

depends for its effect not on its fenestration but on

its elaborate

openwork battlements and its basal frieze of blank encircled

quatrefoils, while internally the E. window is furnished on either side

by the most elaborate of canopied niches, of which that to the north

appears to retain its original sculptural group, representing - again,

according to Dickinson - the Conception of Christ

(Barnack Church, p. 13).

its elaborate

openwork battlements and its basal frieze of blank encircled

quatrefoils, while internally the E. window is furnished on either side

by the most elaborate of canopied niches, of which that to the north

appears to retain its original sculptural group, representing - again,

according to Dickinson - the Conception of Christ

(Barnack Church, p. 13).

Finally, after such detailed architectural description,

the furnishings of the building may be quickly passed over, for the

church contains no significant old woodwork. The font is

thirteenth century work and exceptionally large and heavy, with a great

octagonal bowl decorated with carved foliage and rosettes, supported on

eight trefoil-cusped openwork arches that run round in front of a

central octagonal stem. At the other end of the building, recessed

in the chancel S. wall, the sedilia consists of three equal,

cinquefoil-cusped arches separated by grotesques, one of which was

probably intended to represent a devil and the other depicting a man

with his arms thrown back to clasp the label.

feature

interlacing and what appears to be a cockerel, and the S. wall

also displays a smaller, circular panel at the top of the lower stage,

considered to be the remains of a sundial. Inside the building,

the heavy, round-headed Saxon tower arch is formed of two unmoulded

orders, springing from wide rectangular jambs with imposts like giant

stone sandwiches with the 'filling' recessed in the centre. (See

the N. jamb

below.) These are similar to the

tower arch imposts at St. Beneítís church, Cambridge, and suggest, as

there, an imperfect understanding on the part of the builders of the

structural function of this feature. The quadripartite ribbed

feature

interlacing and what appears to be a cockerel, and the S. wall

also displays a smaller, circular panel at the top of the lower stage,

considered to be the remains of a sundial. Inside the building,

the heavy, round-headed Saxon tower arch is formed of two unmoulded

orders, springing from wide rectangular jambs with imposts like giant

stone sandwiches with the 'filling' recessed in the centre. (See

the N. jamb

below.) These are similar to the

tower arch imposts at St. Beneítís church, Cambridge, and suggest, as

there, an imperfect understanding on the part of the builders of the

structural function of this feature. The quadripartite ribbed

vault underneath the tower, with a round central

hole for the bell-ropes

to pass through, was inserted to provide extra support when the

bell-stage was added. This has two-light, round-arched bell-openings,

with central colonnettes supporting Y-tracery and three orders of

colonnettes at the sides with dog-tooth moulding alongside those.

The late Philip G.M. Dickinson, in his admirable guide to the church,

ascribed this to c. 1200, presumably on the strength of the round

arches, but that may be a little too early (Barnack Church,

revised J. Martin Goodwin, 1990, p. 22).

vault underneath the tower, with a round central

hole for the bell-ropes

to pass through, was inserted to provide extra support when the

bell-stage was added. This has two-light, round-arched bell-openings,

with central colonnettes supporting Y-tracery and three orders of

colonnettes at the sides with dog-tooth moulding alongside those.

The late Philip G.M. Dickinson, in his admirable guide to the church,

ascribed this to c. 1200, presumably on the strength of the round

arches, but that may be a little too early (Barnack Church,

revised J. Martin Goodwin, 1990, p. 22).

its elaborate

openwork battlements

its elaborate

openwork battlements