|

BURSTALL, St. Mary (TM 097 445), SUFFOLK. (Bedrock: Eocene, London Clay.)

A seemingly humble village church with an exceptional N. arcade.

Notwithstanding

its modest external appearance, this interesting church contains one of the

most remarkable arcades in Suffolk, and one, moreover, that poses a

considerable archaeological puzzle. Comprising a chancel, a nave with

a S. porch

and a very broad N.

aisle, and an unbuttressed W. tower, the building is constructed of flint

and chalk rubble, rendered

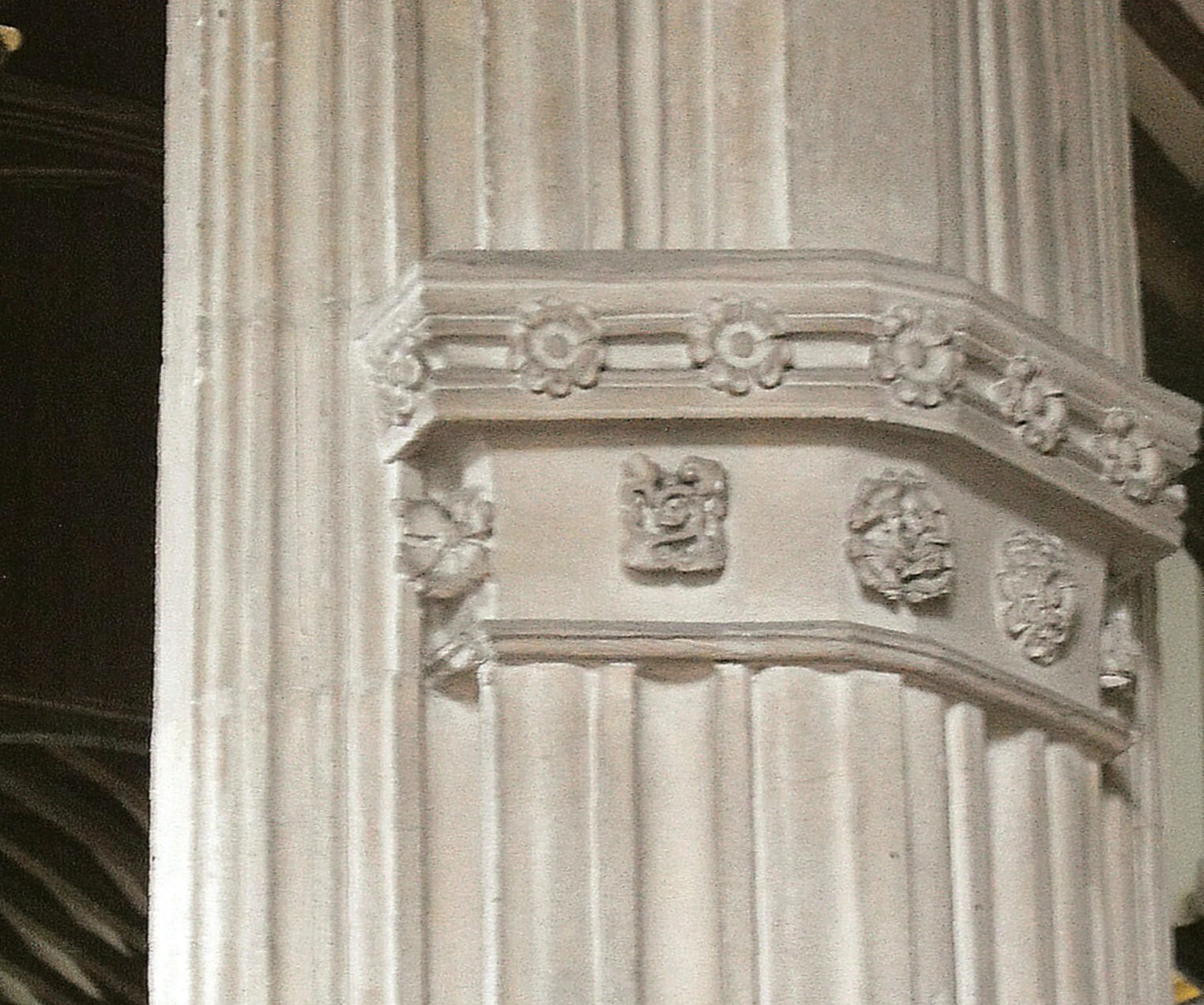

Inside the church, interest moves to the N. arcade. In complete contrast to the N. aisle windows, this is an excellent piece of work, formed of four arches bearing a complex series of narrow mouldings, rising from rhomboidal piers with mouldings continuing down the north and south sides but interrupted towards the openings by capitals finely decorated with fleurons. (See the photograph below left, looking southeast seen from inside the aisle, and the close-up of the westernmost pier, below right.) As Birkin Haward pointed out (Suffolk Mediaeval Church Arcades, Hitcham, The Suffolk Institute of Archaeology and History, 1993, p.188), 'The nearest link might be the Wingfield south chapel piers and arches, but they appear to be some 50 years later'. However, it is instructive at this point to have another look at the aisle windows, this time from within.

Here the rere-arches have narrow engaged side-shafts and a series of narrow mouldings around the heads comparable to those round the arcade, except in the case of the westernmost - the one copying the nave windows opposite - which has neither. The implication is surely be that this is part of an original N. aisle, contemporary with the nave, and that the arcade and two eastern bays of the aisle were reconstructed, perhaps around the time of Wingfield's chapels (c. 1430). That does not explain the misshapen windows in the new work, of course, but a scenario can easily be invented that might do so: the window traceries were designed by another hand, perhaps after the mason that built the arcade had died; these windows were brought here from somewhere else and re-set; or even that the mason who was responsible for the arcade attempted to copy older forms here with which he was not properly familiar, and made a poor job of it... Perhaps the last is the least feasible of these particular theories for was it likely that a mason who designed such a splendid arcades, would perform so badly when designing the windows? Yet even this theory is a measure of how unsatisfactory it seems to assume, along with Birkin Haward, D.P. Mortlock, and even James Bettley (The Buildings of England: Suffolk West, New Haven & London, Yale University Press, 2015, pp. 122 & 124), that the nave, aisle and arcade are contemporary, for surely it is rather more plausible that the windows should attempt to copy earlier forms than that the arcades, without any local precedents, should so dramatically anticipate a later one. Perhaps the reader will devise a better theory...

Moving on to other matters, the half-timbered porch appears to be Perpendicular, but so too does the porch inner doorway with its complex series of waves and hollow mouldings. Inside the church, there is no chancel arch and the tower arch is hidden behind the organ although it can be seen to consist of two orders, each carrying a sunk quadrant.

The easternmost bay of the aisle is divided off by a parclose screen to the south and west, to form a chapel approached up three steps. The screen is a very nice piece, with turned muntins, an inverted round arch above each bay, and a castellated top rail (illustrated right, viewed from the southwest). There is a trefoil-cusped ogee niche either side of the E. window.

The chancel is approached up two steps. The trefoil-cusped window to the south has a lowered sill to act as a modest sedilia and there is a piscina immediately to the east. The reredos and communion rail are modern and the most attractive feature in this part of the church is the excellent Victorian floor tiling (seen at the foot of the page, photographed from the east).

Other woodwork to notice includes the hammerbeam nave roof with carved wall plates and Victorian angels, and the chancel roof framed in five cants (and not scissor-braced as stated by Mortlock). There are also several old pew-backs of various dates, probably from the sixteenth, seventeenth and/or eighteenth centuries.

|

%20-%20burstall%203.jpg) to the south but faced with knapped flint and

limestone to the north, curiously arranged in blocks above the springing

line of the aisle windows aisle. (See the

photographs of the church from the south, above, and the north, below.)

Superficially at least, nearly everything outside appears to

be Decorated (early fourteenth century), the notable exceptions being the N. lancet and three-light E.

window with intersecting tracery in the chancel, which suggest a late

thirteenth century church was refenestrated or partially reconstructed half a century

or so

later: the N. and S. chancel walls are each pierced by a single trefoiled light with an ogee point that cannot be

earlier than c. 1315, the

two-light nave S. windows have reticulated tracery, and the tower has

trefoil-cusped lancet bell-openings and encircled quatrefoils high up in the

stage beneath. But what is one to make of the N. aisle windows? The

three-light, N.

aisle E. window (illustrated left) is a very ugly affair, as if

of curvilinear pattern vaguely remembered and imperfectly understood (yet

D.P. Mortlock calls the aisle windows 'beautiful'! - The Guide to Suffolk Churches,

Cambridge, The Lutterworth Press, 2009, p. 90). The N. windows are

rather better and adopt a variety of forms although

the westernmost window (on the right in the photograph below) is

identical to the windows in the nave S. front (as seen above).

However, the easternmost (below left) has non-standard tracery

composed of three trilobes squeezed in at odd angles inside a rounded

triangle over round-arched cinquefoil-cusped lights, and the middle window (below

centre) and the aisle W.

window, both adopt a more conventional curvilinear tracery formed of a quatrefoil

above two mouchettes, around which, however, two-centred arches of

inadequate radii, manage to nip off the extremities of the mouchettes.

The effect is ornamental perhaps, but scarcely fully competent.

to the south but faced with knapped flint and

limestone to the north, curiously arranged in blocks above the springing

line of the aisle windows aisle. (See the

photographs of the church from the south, above, and the north, below.)

Superficially at least, nearly everything outside appears to

be Decorated (early fourteenth century), the notable exceptions being the N. lancet and three-light E.

window with intersecting tracery in the chancel, which suggest a late

thirteenth century church was refenestrated or partially reconstructed half a century

or so

later: the N. and S. chancel walls are each pierced by a single trefoiled light with an ogee point that cannot be

earlier than c. 1315, the

two-light nave S. windows have reticulated tracery, and the tower has

trefoil-cusped lancet bell-openings and encircled quatrefoils high up in the

stage beneath. But what is one to make of the N. aisle windows? The

three-light, N.

aisle E. window (illustrated left) is a very ugly affair, as if

of curvilinear pattern vaguely remembered and imperfectly understood (yet

D.P. Mortlock calls the aisle windows 'beautiful'! - The Guide to Suffolk Churches,

Cambridge, The Lutterworth Press, 2009, p. 90). The N. windows are

rather better and adopt a variety of forms although

the westernmost window (on the right in the photograph below) is

identical to the windows in the nave S. front (as seen above).

However, the easternmost (below left) has non-standard tracery

composed of three trilobes squeezed in at odd angles inside a rounded

triangle over round-arched cinquefoil-cusped lights, and the middle window (below

centre) and the aisle W.

window, both adopt a more conventional curvilinear tracery formed of a quatrefoil

above two mouchettes, around which, however, two-centred arches of

inadequate radii, manage to nip off the extremities of the mouchettes.

The effect is ornamental perhaps, but scarcely fully competent.